The assassination of Dr. King and the suppression of the anti-war and peace perspectives

“Memory, individual and collective, is clearly a significant site of social struggle.” (Aurora Levins Morales)

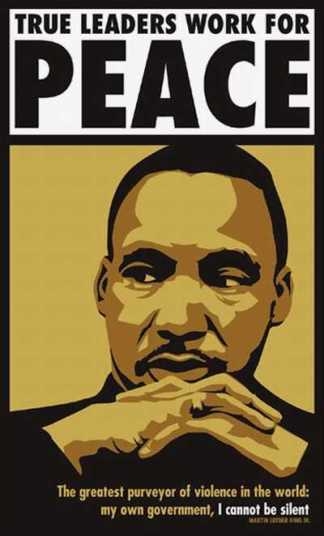

“As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they ask — and rightly so — what about Vietnam? They ask if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government. (Beyond Vietnam – A Time to Break Silence,” Rev. Martin Luther King, Riverside Church, April 4, 1967)

April 4th is an anniversary that I suspect many people in the U.S., including those in government, would prefer that people ignored. On that date 45 years ago, James Earl Ray, supposedly acting alone, murdered Martin Luther King Jr. on a balcony of the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee — silencing one of the great oppositional voices in U.S. politics.

Unlike the celebrations organized around the birthday of Dr. King, with which the U.S. government severs Dr. King from the black movement for social justice that produced him and transforms his oppositional stances into a de-radicalized, liberal, integrationist dream narrative, the anniversary of the murder of Dr. King creates a challenge for the government and its attempt to manage the memory and meaning of Dr. King. The assassination of Dr. King raises uncomfortable questions — not only due to the evidence that his murder was a “hit” carried out by elements of the U.S. government, but also because of what Dr. King was saying before he was killed about issues like poverty and U.S. militarism .

The current purveyors of U.S. violence will find attention to Dr. King’s anti-war and peace position most unwelcome, especially with a black president that has been able to accomplish what U.S. elites could have only dreamed of over the last few decades – the normalization of war-making as a legitimate tool to advance the geo-political interests of the U.S. and its’ colonial allies. So reminding people of Dr. King’s opposition to U.S. warmongering and the collaboration of liberals in that warmongering then and now, produces a strange convergence of political forces from both ends of the narrow U.S. political spectrum that have an interest in suppressing King’s anti-war positions.

When Dr. King finally opposed the war on Vietnam he incurred the wrath of liberals in the Johnson Administration, the liberal philanthropic community, and even a significant number of his colleagues in the clergy. The liberal establishment was scathing in its condemnation of his position and sought to punish him and his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), in a manner similar to their assaults on the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), when it took an anti-war and anti-imperialist position much earlier than Dr. King and SCLC.

In today’s popular imagination of the anti-war and peace movement in the 1960s and 70s, the culprits have been re-imagined as the radical right, symbolized by President Richard Nixon. But it was the Kennedy Administration that escalated U.S. involvement in Vietnam, despite the liberal mythology around his supposed reluctance to do so, and it was Democrat Lyndon Johnson who dramatically expanded the war. When Johnson pulled out of the 1968 presidential race, Hubert Humphrey, the personification of contemporary liberalism, was slated to be the favorite to win the Democratic nomination. Humphrey, along with the rest of the liberal establishment, was firmly committed to Johnson’s war strategy, even in light of growing public opposition.

It should also be remembered that the Chicago police riot of 1968 against anti-war demonstrators took place at the Democratic National Convention, where the protestors were directing their fury at the Democratic Party — which has controlled the Executive Branch during the escalation of almost every major military experience by the U.S. State from the Second World War onwards. The notion of democratic weaknesses on matters of “national defense” owes itself to the historical amnesia of the U.S. population and the successful propaganda campaigns of the more aggressive foreign interventionist elements of the radical right over the years.

Today the array of forces in support of U.S. military aggression is similar to what we saw from the establishment in 1968, except for one important factor: in 1968 there was an organized, vocal anti-war movement that applied bottom-up pressure on the liberal establishment in power and on the Nixon Administration. Today, however, not only have significant elements of the contemporary anti-war and peace movement voluntarily demobilized during the Obama era, many of those individuals and organizations have entered into what can only be seen as a tactical alliance with the Obama Administration and provided ideological cover for imperialist interventions around the world.

Even mainstream human rights organization have facilitated the cover-up, either by their silence on the question of war; by their tacit acquiescence as demonstrated by their pathetic pleading with the attacking powers (usually the West, under NATO) to adhere to the rules of war; or by the construction and articulation of some of the most noxious but effective white supremacist covers for imperialist dominance that may have ever been produced – “humanitarian intervention” and the “right to protect.” Operating from the assumption that the white West are the “good guys” and have a “natural” right to determine which nations deserve to be sovereign, when regimes should be changed, who the international criminals are and what international laws need to be enforced, the political elites have been able to mobilize majority support for imperialist adventures from Iraq to Libya and now Syria. In a nod to the civilizing assumptions of Western modernity that is at the base of the colonialist project justifying these interventions, progressives and even some radicals have muzzled themselves or have even supported these misadventures that entail the West, under the leadership of the U.S., riding in to save people from their “savage governments.” For these activists, if those humanitarian missions result in Western companies managing to secure water, oil and other natural resources and shifting regional power relations to favor the West, well that is just the price to pay for progress. As Madeline Albright said in response to a question regarding the deaths of 500,000 Iraqi children due to U.S. sanctions, “we think the price was worth it.”

It is still about values, consciousness and organization:

“All nationalists have the power of not seeing resemblances between similar sets of facts. A British Tory will defend self-determination in Europe and oppose it in India with no feeling of inconsistency. Actions are held to be good or bad, not on their own merits, but according to who does them, and there is almost no kind of outrage — torture, the use of hostages, forced labour, mass deportations, imprisonment without trial, forgery, assassination, the bombing of civilians — which does not change its moral colour when it is committed by ‘our’ side . . . The nationalist not only does not disapprove of atrocities committed by his own side, but he has a remarkable capacity for not even hearing about them.” ( George Orwell)

The murder of Dr. King was not just the murder of a man but an assault on an idea, a movement and a vision of a society liberated from what Dr. King called the three “triplets” that had historically characterized and shaped the “American” experience – racism, extreme materialism and militarism. On April 4, 1967 in the Riverside Church in New York, exactly one year to the day before he would be murdered, Dr. King took an unequivocal stand in opposition to the U.S. war on the people of Vietnam, and declared that the only way that racism, materialism and militarism would be defeated was if there was a “radical revolution of values” in U.S. society. Today, 45 years later, with a Black president in the White House, racism in the form of continued white supremacy has solidified itself on a global scale; extreme materialism characterizes the desires and consumption patterns of a debt constructed middle class, even as it feels the weight of a national and global economic crisis; and militarism occupies the center of U.S. engagement with the nations of the Global South.

While the current national and global reality could not have been prefigured by political elites in the U.S., the murder of Dr. King and the disarray within the civil rights movement on direction, goals and programs, allowed the government to turn its repressive apparatus to the violent suppression of the Black liberation movement. As the leading element for radical social change in the U.S., the assaults on the Black liberation movement meant that the hope for fundamental change in the U.S. would not be realized. The radical revolution of values that King hoped would transform the country was repackaged by the early 1970s into an individualist, pro-capitalist, debt-constructed consumer diversion. The country began a more dramatic rightward move in the late 1960s that saw the emergence of Nixon; Ronald Reagan; New Democrats; a new and even more virulent ideological construction – neoliberalism; and a uni-polar world, where under Bush and now Obama, the U.S. and its Western colonial allies are able to engage in a form of international gangsterism — invading nations, changing governments and stealing resources, in a manner that is similar to the early years of conquest when they first burst out of Europe in 1492.

The challenge is clear. A de-colonial, revolutionary shift in power from the 1% to the people is the only way Dr. King’s “radical revolution of values” can be realized in a national and global context in which the West has demonstrated that it will use all of its military means to maintain its hegemony. Yet, to realize that shift, the “people” are going to have to “see” through the ideological mystifications that still values Eurocentric assumptions as representing settled, objective realities on issues like democracy, freedom, human rights, economic development and cultural integrity in order to confront the new coalitions of privilege. Dr. King and the black anti-racist, anti-colonialist movements for social justice brought clarity to these moral issues by its example of movement building that sparked struggles for social justice in every sector of U.S. society. That is why sidelining black radical organizations and the black social justice movement has been one of the most effective consequences of the Obama phenomenon.

Today the necessity to stand with the oppressed and oppose war and violence of all kinds has never been more urgent. But that stand cannot be just as individuals. Individual commitment is important, but what Dr. King’s life reaffirmed was the power of movement — of organized and determined people moving in a common direction. That is why the government so desperately attempts to disconnect Dr. King from the people and the movement that produced him and to silence any opposition to its colonialist violence. The example of movement building and struggle is an example that has to be brutally suppressed, as witnessed by how the Obama Administration moved on the Occupy Wallstreet Movement once it became clear that they could not co-opt and control it.

Consciousness, vision, an unalterable commitment to privileging principle over pragmatism and a willingness to fight for your beliefs no matter the odds or forces mounted against you – these are the lessons that all of us who believe in the possibility of a new world should recommit to on April the 4th. Internalizing and passing that lesson on through a culture of resistance and struggle ensures that one day all of us will be able to create societies freed from interpersonal and institutional violence and all forms of oppression in our own promised lands.

Ajamu Baraka is a long-time human rights activist and veteran of the Black Liberation, anti-war, anti-apartheid and Central American solidarityMovementsin the United States. He is currently a fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies. Baraka is currently living in Cali, Colombia.